Visitor Pattern Problem Space

We examine here a very important pattern, the Visitor Pattern.

The Visitor Pattern is used to represent an operation to be performed on the elements of an object structure. The pattern lets you define new operations without changing the classes and elements on which you operate.

This is an example of the “open-closed” principle: Classes should be open for extension but closed for modification. The Visitor Pattern allows us to extend the behavior of our class structure by later adding new functionality, but without having to invade all the classes involved.

Imagine writing a program for symbolic algebra manipulations. Then there are some considerations we have to take into account:

As some of the forms contain sub-expressions, our code would need to be recursive, i.e. to be able to call itself on the subexpressions. For instance to print an addition, we would need to first print the left operand, which may be a whole complicated expression, then print the “plus” sign, then print the right operand.

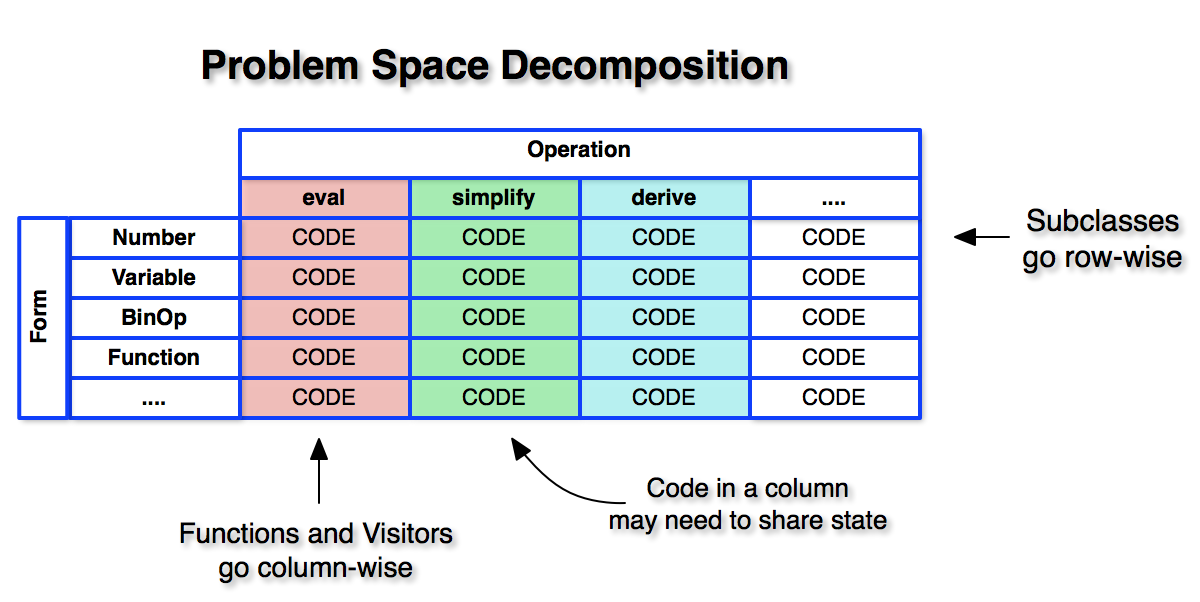

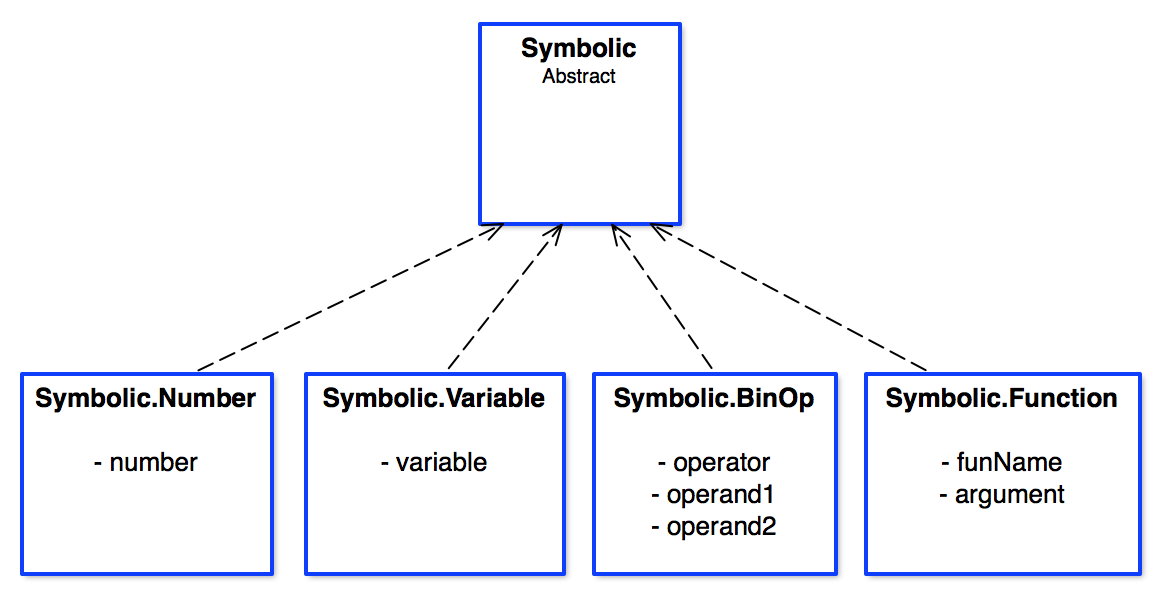

In any case, we will need some way for the code to recurse on the structure of the expression.We can visualize this situation as a rectangular arrangement, with forms as rows and operations as columns:

Visitor Pattern Problem Space

One important thing to note is that it is desirable that all the code related to the same operation stay together. The code for evaluation of a binop has little to do with the code for printing that binop, but it has more to do with the code for evaluating a func case, or a variable case. In other words, the coherence is stronger between code for the same operation but different forms, than between code for the same form but different operations.

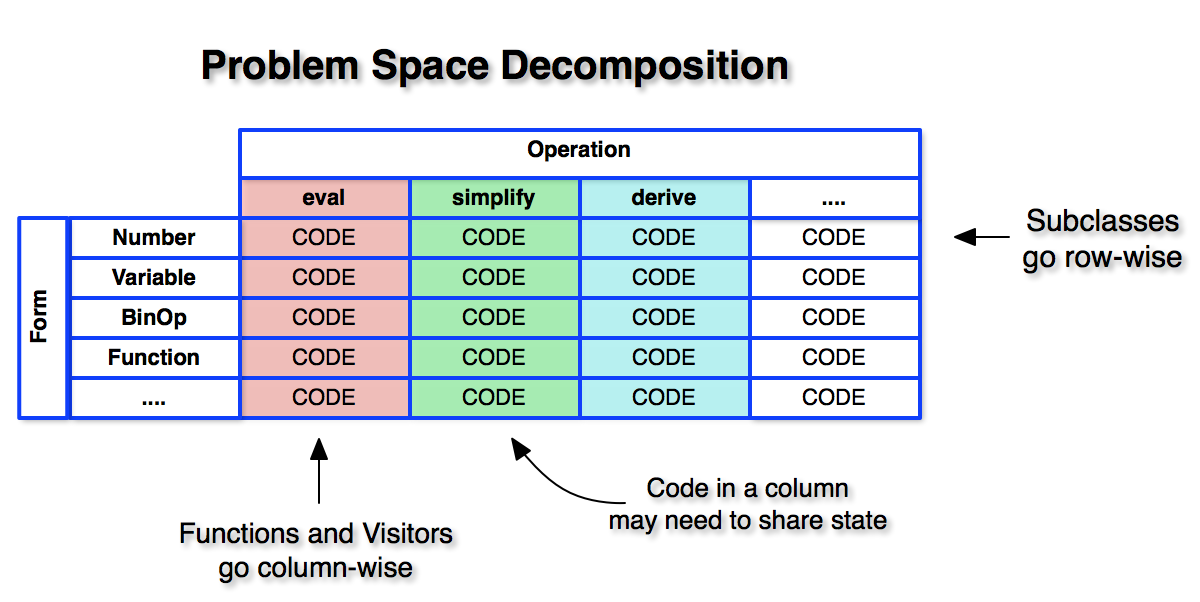

If we imagine a particular expression, we can envision it as a sort of tree. For instance it might start with a binop at the root, and the operand1 might be binop itself, operand2 might be a number, and so on. The picture shows such an example, as well as the path that our evaluate’s code might have to take through this tree structure.

Expression Tree

We start by discussing how a non-object oriented approach to this problem would go. We will use Javascript objects thought of as dictionaries. You can consider them a little bit like C structs. With that in mind, we could do something like the following:

type field.type field, the object will contain further fields (e.g. operator/operand1/operand2 if the type was “binop”).type:function makeNumber(n) {

return {

type: 'number',

value: n

};

}

function makeBinOp(op, left, right) {

return {

type: 'binop',

operator: op,

operand1: left,

operand2: right

};

}

// ... other similar "constructors", one for each form

//

//

function evaluate(expr) {

switch (expr.type) {

case 'number': // ... handle number case

case 'binop':

// ... handle binop case

// ... Will involve evaluate(expr.operand1) etc

default: throw new Error('Unknown expression type: ' + expr.type);

}

}

// ... functions for other operationsOne advantage of this approach is that it can keep all the code related to the evaluation in one place. There are however some disadvantages:

Harder to maintain state. We have to pass any state that we want to maintain as further arguments to the call, and remember to pass that state onto any recursive calls.

Alternatively, we can create the evaluate function within some scope on which some variables are initialized, and then each call can access them. This could look like this:

function evaluate(initialExpr) {

var theActualFunc, state;

// ... initialize state here

theActualFunc = function(expr) {

switch (expr.type) {

case 'number': // ... handle number case

case 'binop':

// ... handle binop case

// ... Will involve theActualFunc(expr.operand1) etc

default: throw new Error('Unknown expression type: ' + expr.type);

}

};

return theActualFunc(initialExpr);

}switch code actually accounts for all cases and has not mistyped a case. If these “magic values” are to change in the future, we must keep track of that change in all the various places where such a switch is being used.evaluate are to be, or offers any way to automatically check that input.No clear information hiding. The full details of the individual structures are exposed to the various functions we are writing. If we change anything in the structure generators, we must account for that change in all the consumers.

In programming languages that follow a stronger functional programming paradigm, most of these problems are alleviated. In a language like Javascript that lacks static typing, algebraic types and pattern matching, they are important problems and really none of the methods will be able to fully alleviate them.

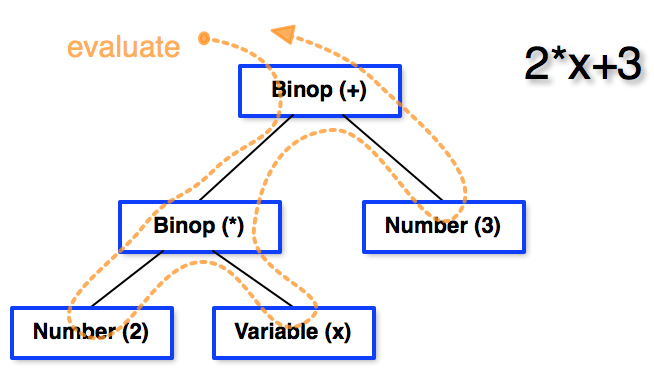

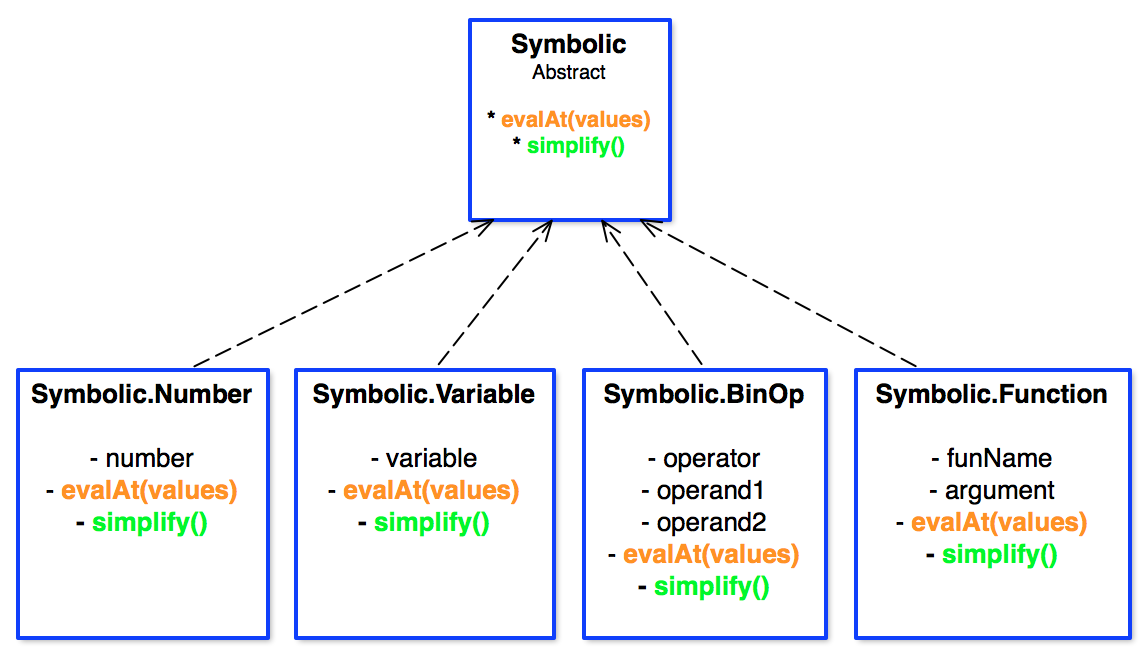

Here’s how an object-oriented approach to designing the problem space might go. The first goal would be to provide a somewhat common interface to all the different forms. To that tned, we have an overall class called Symbolic that represents in an abstract sense a symbolic expression. Then we have numerous subclasses of it, one for each kind of symbolic expression. So the class diagram might look like this:

Symbolic Expression class structure

Now what we are interested in is adding lots of operations we can perform for such symbolic expressions, as we saw earlier. The question is how we would go about implementing these operations.

A straightforward approach is to add a method in each of the subclasses. The graph would then look like this:

Implement operations in the classes

This approach certainly has some advantages, most notable amongst them is very strong encapsulation: Each subclass needs to worry about what is going on within itself, and noone else needs to know anything about it.

This approach has a number of important drawbacks:

Violation of open/closed principle. This principle says that “classes/modules/etc” should be open for extension, but closed for modification. In other words the principle says that we should be able to extend a class’ functionality without having to modify the class. In our particular instance we cannot add a way to evaluate an expression without modifying the code for each subclass and adding an evalAt method to them, and correspondingly change the interface for all the classes.

This is the key benefit of the visitor pattern we will see. It is to be used when we want to have the ability to add functionality/operations to classes without modifying them.

So how can we add functionality to the subclasses without modifying them? One approach would be to subclass them. So for instance in order to introduce an evalAt method we would create a subclass Symbolic.EvaluatableNumber, of Symbolic.Number, and the same for all the other subclasses. We would end up with 4 new subclasses. And if we want to add a simplify method, we would need another 4 (or 8 if we also wanted instances with simplify but no evalAt). And so on. Obviously not a very elegant solution. We will quickly step away from it and keep our distance.

Another somewhat straightforward approach is to do dispatch to the appropriate code, based on each subclass. So at any point we ask the expression what class it is, and we direct it accordingly. This is similar to the functional approach we mentione earlier, and it suffers from similar problems. It might look like this:

// Call like: evalAt({ x: 5, y: 2 })(expr);

var evalAt = function(values) {

// Function that traverses a given expression for a given set of values

var evaluate;

evaluate = function(expr) {

if (expr instanceof Symbolic.Number) {

return expr.number;

} else if (expr instanceof Symbolic.Variable) {

return values[expr.variable];

} else if (expr instanceof Symbolic.BinOp) {

return doOperation(expr.operator,

evaluate(expr.operand1),

evaluate(expr.operand1));

} else if (expr instanceof Symbolic.Function) {

return applyFunction(expr.funName, evaluate(expr.argument));

} else {

throw new Error('Expression is not one of the known subclasses');

}

};

return evaluate;

};Let us discuss the drawbacks of this approach:

Class detection and dispatch. The above method asks an object what class it is and acts accordingly. In general doing so is frowned upon, as it breaks encapsulation. You are typically meant to call an object’s method, and depending on what class the object is the system will run a different method for each kind of class. This is the main mechanism called dynamic dispatch: The code that runs as the result of a line like o.foo() depends on what object o is when that code actually runs. Bypassing that mechanism goes against the grain of object-oriented programming.

Dispatch logic conflated with business logic. The code that tells us how to handle each case is mixed together with the code for deciding which case to handle. Ideally these should be separated.

This solution follows the previous one, except that it places each case’s code in a separate method. So it could look like so:

function Evaluator(values) {

this.values = values

}

Evaluator.prototype = {

evaluate: function(expr) {

if (expr instanceof Symbolic.Number) {

return this.evaluateNumber(expr);

} else if (expr instanceof Symbolic.Variable) {

return this.evaluateVariable(expr);

} else if (expr instanceof Symbolic.BinOp) {

return this.evaluateBinOp(expr);

} else if (expr instanceof Symbolic.Function) {

return this.evaluateFunction(expr);

} else {

throw new Error('Expression is not one of the known subclasses');

}

},

evaluateNumber: function(expr) {

return expr.number;

},

evaluateVariable: function(expr) {

return this.values[expr.variable];

},

evaluateBinOp: function(expr) {

var v1 = this.evaluate(expr.operand1);

var v2 = this.evaluate(expr.operand2);

// Could have the doOperation logic here

return doOperation(expr.operator, v1, v2);

},

evaluateFunction: function(expr) {

// Could have the applyFunction logic here

return applyFunction(expr.funName, this.evaluate(expr.argument));

}

};This gets us a bit closer to the visitor pattern. Each case is now in a separate function, so it is a tad easier to see if we have missed any (and in a statically typed language like Java, the compiler would not let us miss a case as we have to fill in all the instance methods). Still, no guarantee that all the instance methods are accessed from the evaluate method.

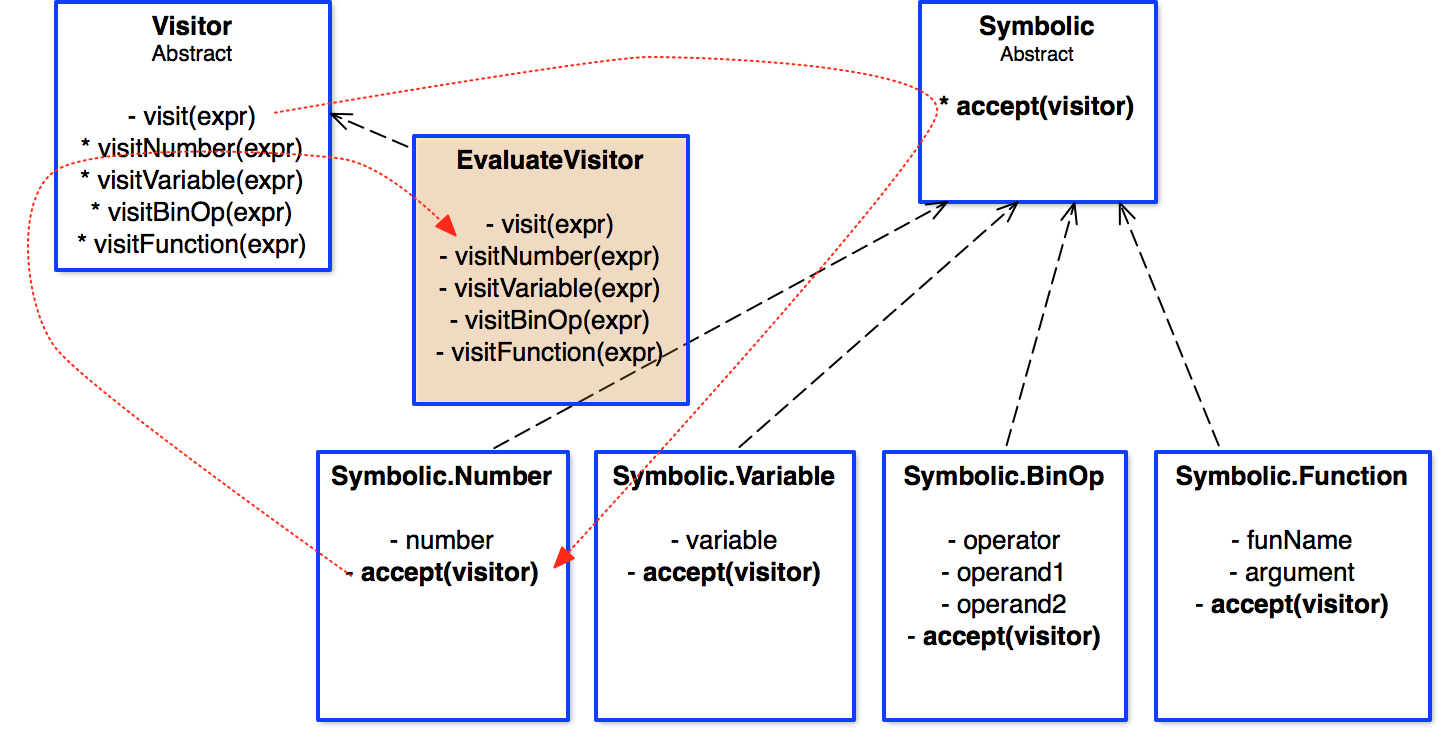

The visitor pattern is a variation of this code that avoids the deep case statement, and lets the system do that dispatch instead.

The visitor pattern works as follows:

Evaluator, Simplifier, TeXConverter etc.visit methods, one for each subclass. So in our example we would have visitNumber, visitVariable etc. It is important to use these names, instead of more specialized ones like the evaluateNumber we used above.Each subclass of the structure implements a single method, called accept. This method takes as input a visitor, and turns around and calls that visitor’s appropriate method depending on what kind of subclass we’re dealing with. For instance in the Symbolic.Number class we would find:

Symbolic.Number.prototype.accept = function(visitor) {

return this.visitNumber(visitor);

};The visitor typically also contains a visit method which turns around and calls the object’s accept method:

Evaluator.prototype.visit = function(visitor) {

return visitor.accept(this);

};If the Evaluator subclasses a Symbolic.Visitor class, the implementation of visit could in fact be there.

So essentially for a number this would generate the following sequence of calls:

// The evaluator instance wants to evaluate the expression.

evaluator.visit(expr)

// This call becomes:

expr.accept(evaluator);

// And that in turn becomes:

evaluator.visitNumber(expr); // Depends on the class of expr.Here is a picture:

The visitor pattern illustrated

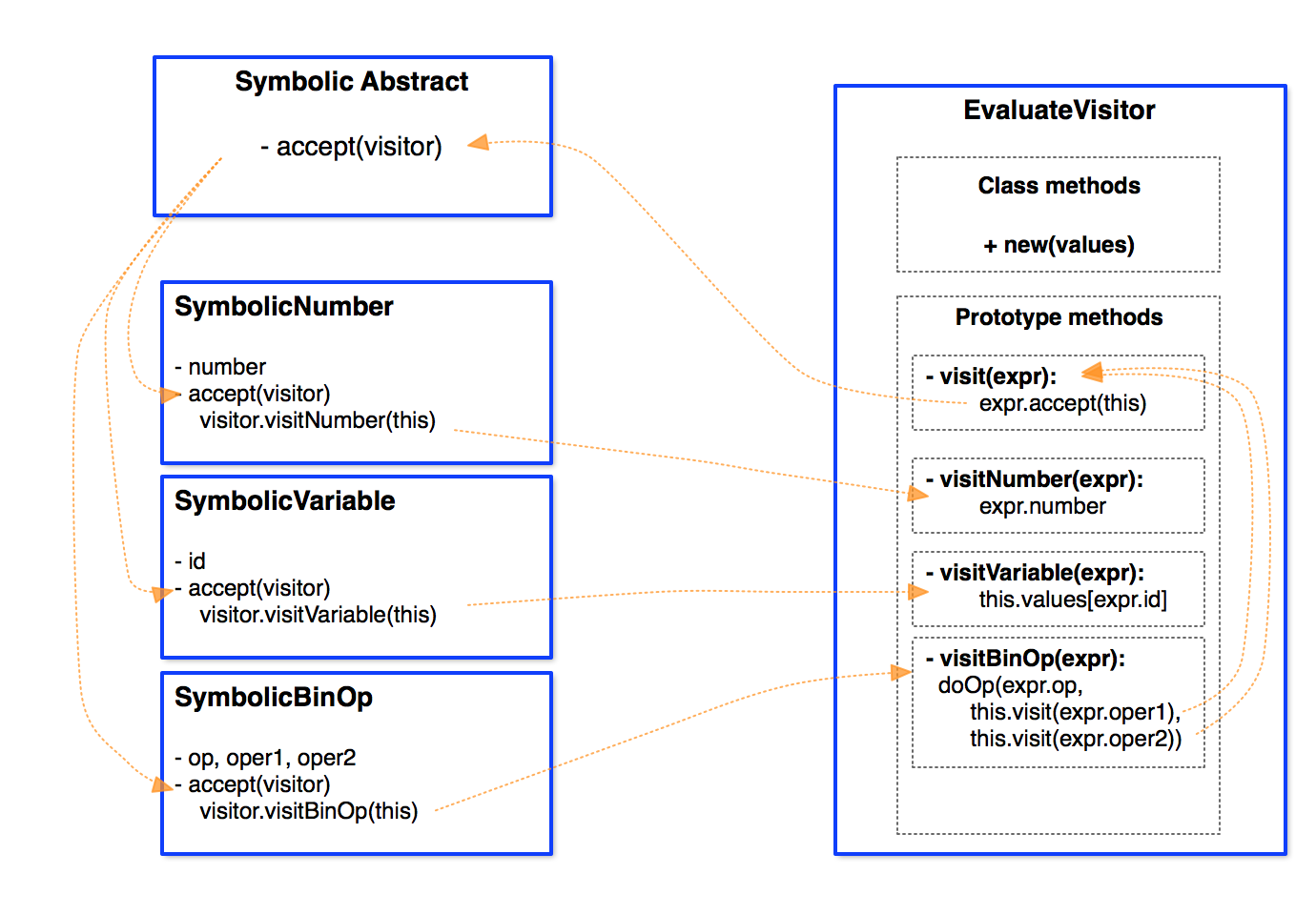

And here is a more detailed view of the dispatch logic.

The visitor pattern dispatch details

The big advantage of this method is that it requires a single function to be added to each subclass, namely accept. Then all sorts of visitors can be written, but they all use that accept method and nothing else from the classes.

It does have an important drawback however: Adding a new subclass to the Symbolic expression set becomes nontrivial. Instead of simply adding one new subclass and implementing all its needed methods, we now have to go into every single visitor class and add a visitTheNewExpressionType method.

The visitor pattern allows us to set up an interface where we can easily add operations to a fixed set of objects/classes without having to change the class implementations.

On the other hand, changing the set of objects/classes by adding new types of objects is harder to do with the visitor pattern, as it requires reworking the implementation of all the visitors.

In other words, the visitor pattern is good when you have a fixed set of classes of objects that need to support a varying set of operations on them.

It makes adding new operations easy.

You can find two examples of the visitor pattern:

An expression language test page, which describes a small language for algebraic expressions, where the allowed expressions are:

x=... for later use)x+2)ln(x))The Symbolic Expression language we have been describing.