Section 2.2

Practice problems (page 128): 2.7, 2.10, 2.11, 2.12, 2.13, 2.18

Challenge: 2.20, 2.25

Pushdown automata are also some times called “stack machines”. They are an extension of finite automata, where we are allowed a “stack” to store information. We should start with a quick reminder on stacks:

A stack is a structure on which you can do exactly two things:

- You can add a new element at the “top”. This is called a push.

- You can remove and look at the element at the top. This is called a pop.

A stack in our usage does not allow you to see what elements are under the top element.

Stacks start their “life” empty, and grow and shrink in size as we push and pop elements in them. The key thing to remember is the LIFO behavior: The last thing in is the first thing out.

In OCAML we could implement a stack by simply using a list, where new elements are prepended to the list and popping removes the head of the list and keeps the tail.

The idea of pushdown automata is similar to that of finite automata:

So formally, a pushdown automaton is defined thus:

A pushdown automaton is a 6-tuple \((Q,\Sigma,\Gamma, \delta, q_0, F)\) where:

- \(Q\) is a finite set of states.

- \(\Sigma\) is a (finite) alphabet (the terminals in our CFG case).

- \(\Gamma\) is the (finite) set of possible stack symbols. Typically this will include the terminals, the nonterminals and occasionally other special symbols.

- \(q_0\in Q\) is the start state.

- \(F\subset Q\) is the set of accept states.

- \(\delta\colon Q\times\Sigma_\epsilon \times \Gamma_\epsilon \to \mathcal{P}\left(Q\times\Gamma_\epsilon\right)\) is a (nondeterministic) transition function.

Note that we only look at nondeterministic pushdown automata. Deterministic pushdown automata are NOT equivalent to them, but we will not consider them here. Essentially, because of the presence of the stack, we cannot do away with non-determinism the way we did with NFAs.

Computation in a pushdown automaton goes as follows:

Computation in a pushdown automaton:

- The automaton starts at the start state \(q_0\) and with an empty stack and at the beginning of the input.

- When on a state \(q\), the automaton nondeterministically chooses one amongst options coming from 4 sets:

- One of the options in \(\delta(q, \epsilon, \epsilon)\). In this case it does not consume any input and it does not pop anything from the stack (but it might push something).

- One of the options in \(\delta(q, a, \epsilon)\). In this case the next input should be \(a\) and it will be consumed, and nothing is popped from the stack.

- One of the options in \(\delta(q, \epsilon, s)\). In this case no input is consumed, but the top of the stack should be \(s\) and it is popped.

- One of the options in \(\delta(q, a, s)\). In this case the next input must be \(a\) and is consumed, and the top of the stack must be \(s\) and it will be popped.

- If the automaton has consumed all input and has made it to an accept state (possibly following some of the \(\epsilon\)-input possibilities above once it has consumed all input), then it accepts the string.

The language of the automaton is the set of all strings that the automaton accepts.

For example consider the language:

\[L = \left\{ x^ny^m \mid n \geq m \geq 0 \right\}\]

So the language allows any number of \(x\)’s followed by no more than that many \(y\)’s. Here is an automaton that will recognize the language. We will use the stack to count how many \(x\)’s we have seen that have not been matched by corresponding \(y\)’s.

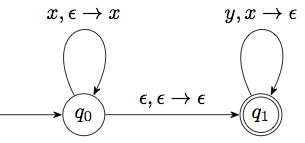

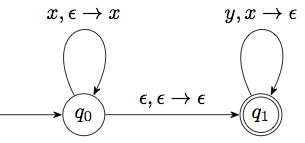

Here is a visual representation:

Now let us try a slightly more difficult language:

\[L = \left\{ x^ny^n \mid n \geq 0 \right\}\]

This is a bit different than the previous example. In the previous example we did not need to know that the stack was empty before returning. In fact there might be a bunch of \(x\)’s left in the stack. All we had to make sure is that we don’t add a \(y\) unless there was an \(x\) to match it.

This case is different. We will need to know when we have taken all the \(x\)’s out of the stack, because it is only at that time that they are matched to the \(y\)’s. But by default there isn’t really an automatic mechanism for doing that. But we can build one ourselves, and from now on we will do these steps without thinking about them much:

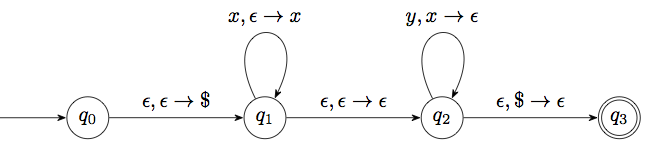

How to check for empty stack:

- Add a new stack symbol, not existing in \(\Gamma\). We denote it by \(\$\).

- Add a new start state, with a transition \(\epsilon,\epsilon\to\$\) to the previous start state. This adds a symbol at the bottom of the stack. Running into that symbol means the stack is empty.

- At any place where you need to test for end of input, add a transition \(\epsilon,\$\to \epsilon\) to a new final state.

Let us illustrate this with a pushdown automaton for the language \(L\) described above:

Exercise 1: Work out a PDA for the language that consists of all palindromes.

Exercise 2: Work out a PDA for the language that consists of all matched parentheses (e.g. (()(()()))).

Exercise 3: Work out a PDA for the language that consists of an equal number of \(x\)s and \(y\)s (but not requiring all \(x\)s before all \(y\)s).

There are some convenient things we can do to simplify a PDA, that will be critical for what we will do next. First of all, we can of course assume that there is only one accept state, by instead \(\epsilon\)-transitioning to a new state from all the accept states like we would do in an NFA. But the nice thing in our case is that we can also empty the stack first:

For any PDA there is an equivalent PDA which only accepts with an empty stack.

The process for constructing this new PDA is somewhat simple: