The Internet and the Web did not have to exist. They come to us courtesy of misallocated defense money, skunkworks engineering projects, worse-is-better engineering practices, big science, naive liberal idealism, cranky libertarian politics, techno-fetishism, and the sweat and capital of programmers and investors who thought they’d found an easy way to strike it rich.

The result is, amazingly, a simple, open (for now), almost universal platform for networked applications. This platform contains much of human knowledge and supports most fields of human endeavor. We think it’s time to seriously start applying its rules to distributed programming, to open up that information and those processes to automatic clients. If you agree, this book will show you how to do it.

REST stands for "REpresentational State Transfer", which is a bit of a mouthful, and is best described in terms of the goals it proposes for a Web API design. A key underlying principle is that REST attempts to use as much of the HTTP protocol as possible to communicate information. This is in contrast to other standards that place all pertinent information about the request mostly in the request's body.

A key consideration when considering an HTTP request is the difference between method information and scoping information.

Here are some key elements of a REST protocol:

Chapter 4 of Restful Web Services discusses an approach to achieve RESTfullness, that the authors term "Resource Oriented Architecture". It emphasizes the concept of resource, i.e. any part of the service important enough to be addressed by itself.

Any resource should be addressable via at least one URI (though it is possible for multiple URIs to refer to the same resource). This is a key feature afforded to us by the use of the web. Statelessness is another key part of this: That URI should be all the information you need to get to the resource. The server should not have to remember anything from your prior activities on the site.

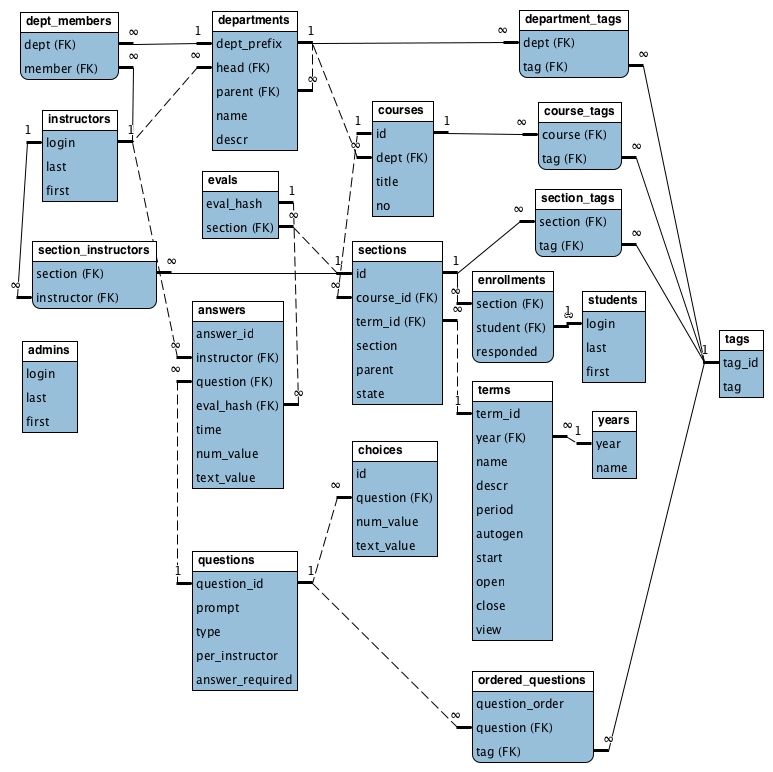

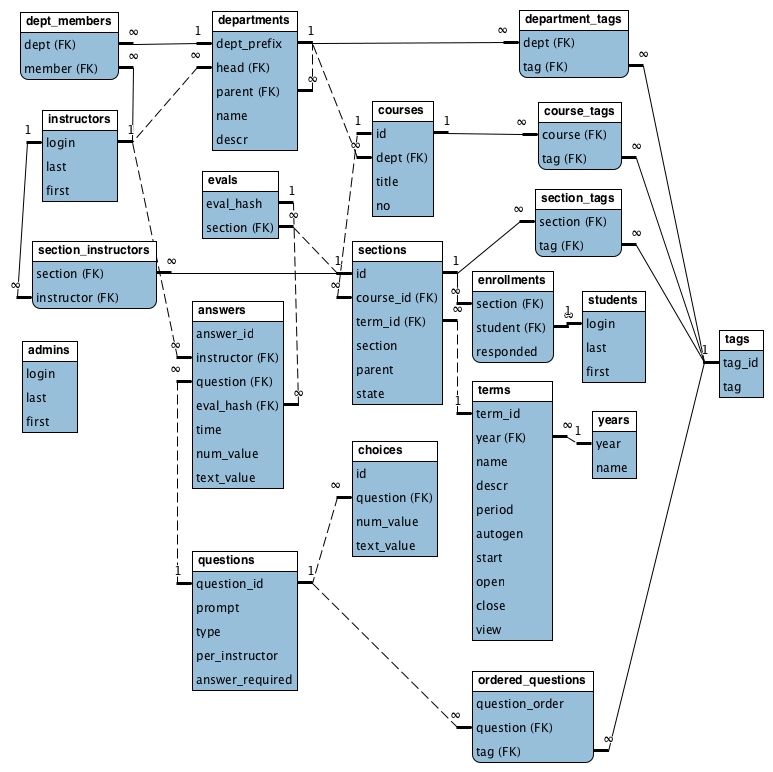

As an example let us consider the following entity-relation graph for the student evaluations database:

There are numerous resources in this instance. We name just a few:

| Resource | Description | URI Scheme | Properties | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| students | Represents the list of students | /student | students | |

| student | Represents a student | /student/{login} | login first last | enrollments |

| section | Represents a specific offering of a course | /section/{year}/{term}/{no} | state | course enrolled year term |

Inclass activity: Consider what other resources we have, what URIs we might use for them, and what links to other resources they would have.

In the above example we also see another key feature of a RESTful design, using the "hypermedia" feature of the HTTP protocol. It may be a trivial thought these days, but the fact that we can link different pages together is key. For instance in the example above the student resource would include in it a link to the enrollment resources for that student. RESTful resources are fundamentally linked to one another, so that a client of our service can navigate their way by following these links, in much the same way that a user of a website navigates taht site by following links.

Another key feature of a RESTful design is the use of a common "interface", via consistent use of the HTTP method verbs:

Used for essentially two purposes. One is to create "subordinate resources". For instance, performing a POST in the "students" resource earlier could be used to create a new student. It would be similar in effect to performing a PUT at the student resource directly. In order to determine which of the two should be used, we need to ask who is responsible for generating the new resource's "name" and URI. If it is the client, then a PUT is used; If it is the server, then a POST on the parent is used.

The second use of POST is to update information of a resource. For example if a student changes name, we would update that information via a POST request to the specific student's URI.

In both usages the key is that POST is used to update subordinate information for a resource, be they resources themselves or just properties/data associated with the resource.

Two important concepts that emerge from proper usage of HTTP methods are safety and indempotence.

A safe request is one that does not change the server state. For instance in a proper design, all GET and HEAD requests are safe, as they simply fetch information. By constrast, DELETE, PUT and POST are not safe, as they are fundamentally designed to change the server state.

This may seem like a minor point, but it has some important consequences. In earlier days, before some of these notions were crystallized, GET requests were often used to delete resources. For instance a GET request to "/yourresourceURI/delete" would delete the resource. Around the same time some of the popular browsers attempted to speed up your work by following via GET any links in a webpage, and prefetching them so they can show them to the user faster should the user click one of those links. These browsers had no way of knowing whether the GET request they made would end up deleting something or not. Disaster ensued. We need to be able to trust that GET operations are safe, so that we an perform them as a way of prefetching without worrying about changing server data.

Idempotence is a slightly different idea. An operation is idempotent, if repeating it has no effect. Sending two identical DELETE requests for example should result in the second request doing nothing; the resource was already deleted from the first request. In general we expect GET, HEAD, DELETE and PUT to all be idempotent. This allows clients to safely send such a request a second type and not worry about the effect to the server.

THe idempotence of PUT should be kept in mind. PUT creates or replaces a resource, it does not update it in the way that POST does. You can send a PUT request multiple times and expect the effect to be the same as if you used it once, in the same way that having multiple "x=5" assignments is the same as having only one such assignment. By contrast, POST is more analogous to a "x++" statement. Multiple POSTs could have accumulated effects.